|

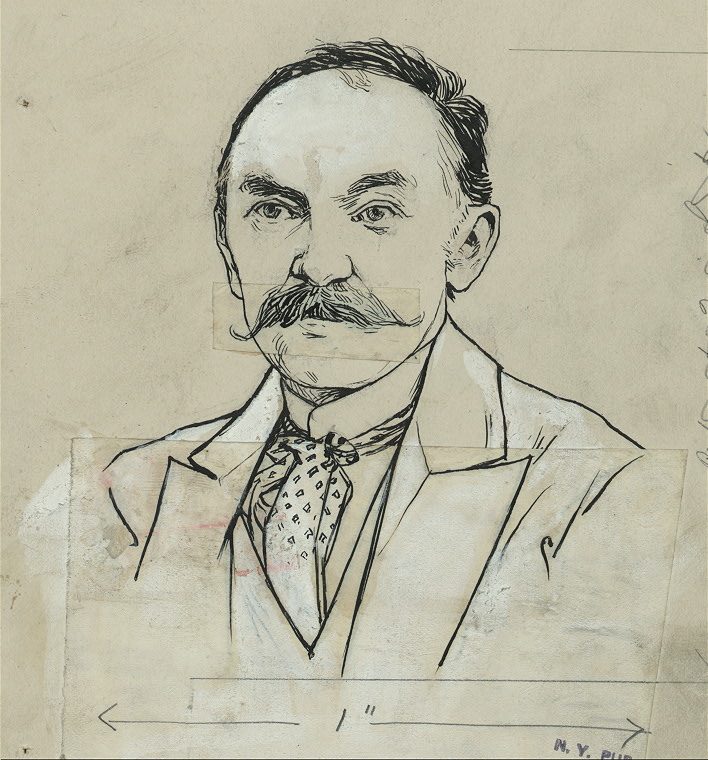

| An 1865 portrait of the poet Algernon Charles Swinburne, perhaps the greatest single literary influence on Thomas Hardy. |

Hardy's literary pedigree is novel (for his time) in that it is a lineage inherited from his mother, Jemima. Ironically, there is evidence supporting the idea that Jemima was an avid reader but could not write much beyond signing her own name. It has been suggested that Thomas inherited his mother's love of reading due to his own ill health in childhood but there remains the (possibly apocryphal) story that he could read before he was three. It is plain that Jemima's love of reading created an environment where books were prioritized as valuable for the children of which Thomas was the eldest.

It should come as little surprise that Thomas's library was peppered with a mixture of non-fiction and Biblical related literature but his mother's eclectic tastes also dropped a few tasty morsels such as a translation of Virgil's Aeneid and Samuel Johnson's Rasselas.

As he grew older, we see more primers and subject books appearing, with interests in history, languages and grammar already identifiable. Millgate's biography also mentions him reading works by historical fiction writer Harrison Ainsworth, Dumas and some of the Shakespearean tragedies.

It was in Dorchester, while apprenticing with architect John Hicks, that Hardy's intellectual world expanded the most impressively under the influence of his close-friend Horace Moule. Moule introduced him to many of the revolutions in natural science and philosophy that would shake the foundations of the Christian faith in the 19th century. Moule also encouraged him in his Greek studies but, despite Hardy's ambitions to join the clergy by attending university, saw his efforts better directed toward the course he was on to become a respectable architect.

Hardy may have moved to London in 1862 (aged 21) in order to further his career as an architect but it also marks our first sense of his having considered writing as an alternative to his first dream of furthering his education. His readings alternated between classics like Shakespeare and books designed to expand his mode of thinking on topics including logic, economy and philosophy -- all suggested by Moule with whom he was still in conversation.

By 1864, he was placing small pieces in publication while considering poetry as a vehicle for his creativity. His poetic models at that time were many including: Milton; Scottish poet James Thomson, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Edmund Spenser, Robert Burns, Lord Byron, Wordsworth, Shelley and Tennyson. He also appears to have discovered his closest poetical forebear in terms of influence, A.C. Swinburne, specifically his Poems and Ballads.

What seems most interesting in this exploration of the books that shaped Thomas Hardy is the lack of traditional novels among them. Though Hardy would study novels as he embarked upon his career as a writer of them, he did so as an architect would -- dissecting them for their structure and narrative devices that he might be able to replicate said devices as was necessary in his own writing. For Hardy, novels were a means to the end of earning a living as writer and not necessarily the source of his inspiration to write in the first place. For that, it is wiser to look to the oral storytelling traditions of his home and family from which he would derive so much of the material of his own novels.